The announcement by Iran and Saudi Arabia that they are re-establishing diplomatic ties could lead to a major realignment in the Middle East. It also represents a geopolitical challenge for the United States and a victory for China, which brokered the talks between the two longstanding rivals.

Under the agreement announced on Friday, Iran and Saudi Arabia will patch up a seven-year split by reviving a security cooperation pact, reopening embassies in each other’s countries within two months, and resuming trade, investment and cultural accords. But the rivalry between the two Persian Gulf nations is so deeply rooted in disagreements about religion and politics that simple diplomatic engagement may not be able to overcome them.

Here is a look at some of the key questions surrounding the deal.

Why is this important?

The new diplomatic engagement could scramble geopolitics in the Middle East and beyond by bringing together Saudi Arabia, a close partner of the United States, with Iran, a longtime foe that Washington and its allies consider a security threat and a source of global instability.

In the years since, Saudi Arabia has encouraged a harsh response from the West toward Iran’s nuclear program and even established diplomatic back channels to Israel, the strongest anti-Iran force in the Middle East, partly aimed at coordinating ways to confront the threat from Tehran.

How the breakthrough announced on Friday would affect Saudi Arabia’s participation in Israeli and American efforts to counter Iran was not immediately clear. But the resumption of diplomatic relations between the two regional powers marked at least a partial thaw in a cold war that has long shaped the Middle East.

What could the impact be across the Middle East?

Since they broke off diplomatic relations in 2016, the leaders of Iran and Saudi Arabia have regularly denounced each other. Tehran has accused the Saudis of backing terrorist groups such as the Islamic State, and Saudi Arabia has blasted Iran’s support for a network of armed militias across the Middle East.

The Saudi-Iranian rivalry has underpinned conflicts across the Middle East, including in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Yemen.

While the breakthrough announced on Friday took many observers by surprise, Saudi and Iranian intelligence chiefs have been meeting in Iraq in recent years to discuss regional security. A more formal diplomatic engagement may provide avenues for the two regional powers to make further progress on cooling regional flash points.

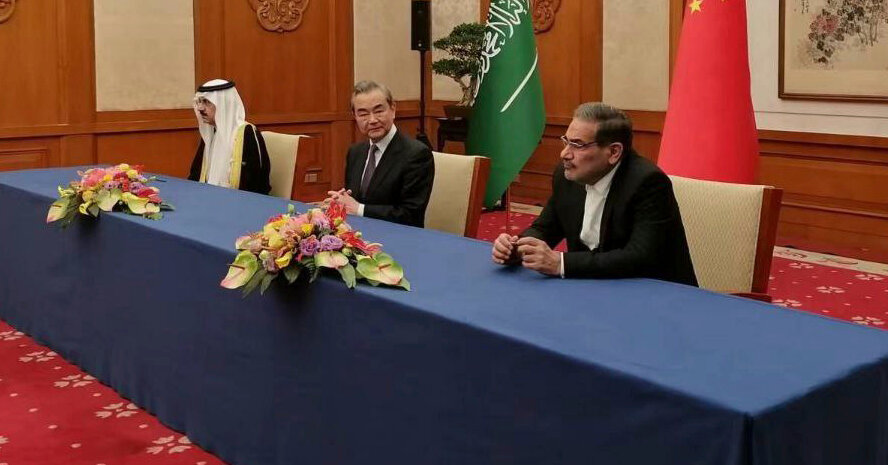

What was China’s role?

Iran and Saudi Arabia announced the agreement after talks hosted by China. Beijing maintains ties with both Middle Eastern countries, and the breakthrough highlights its growing political and economic clout in the region, which has long been shaped by the influence of the United States.

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, visited Riyadh, the Saudi capital, in December, a state visit that was celebrated by Saudi officials, who often complain that their American allies are pulling away.

“China wants stability in the region, since they get more than 40 percent of their energy from the Gulf, and tension between the two threatens their interests,” said Jonathan Fulton, a nonresident senior fellow for Middle East programs at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

Regional leaders have also noted their appreciation that China, which maintains a policy of “noninterference” in other countries’ affairs, avoids criticizing their domestic politics and does not have a history of sending its military to topple unfriendly dictators.

The announcement also reflects China’s desire to play a bigger diplomatic role on the world stage. Beijing has presented what it calls a “Global Security Initiative” and, last month, introduced a peace plan for Ukraine. Both the security initiative and the Ukraine proposal have been panned in the West for lacking concrete ideas and for ultimately promoting Chinese interests.

What could it mean for the United States?

News of the deal, and particularly Beijing’s role in brokering it, alarmed foreign policy hawks in Washington.

“Renewed Iran-Saudi ties as a result of Chinese mediation is a lose, lose, lose for American interests,” said Mark Dubowitz, the chief executive of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington-based think tank that supports tough policies toward Iran and China.

He said it showed that Saudi Arabia lacks trust in Washington, that Iran could peel away U.S. allies to ease its isolation and that China “is becoming the major-domo of Middle Eastern power politics.”

But if the agreement reduces tensions in the region, that could ultimately be good for a Biden administration that has its hands full with the war in Ukraine and a sharpening superpower rivalry with China.

Trita Parsi, an executive vice president of the Quincy Institute, a Washington group that supports U.S. restraint overseas, said, “While many in Washington will view China’s emerging role as a mediator in the Middle East as a threat, the reality is that a more stable Middle East where the Iranians and Saudis aren’t at each other’s throats also benefits the United States.”

The White House rejected the idea that China was filling a void left by the United States in the Middle East. “We support any effort there to de-escalate tensions in the region,” said John Kirby, a spokesman for the National Security Council.

He questioned Iran’s commitment to a true rapprochement with a longtime adversary, however.

“It really does remain to be seen whether the Iranians are going to honor their side of the deal,” Mr. Kirby said. “This is not a regime that typically honors its word. So we hope that they do.”

What could it mean for Israel?

The news prompted surprise and anxiety in Israel, which has no formal ties with Iran or Saudi Arabia. But while Israeli leaders see Iran as an enemy and an existential threat, they consider Saudi Arabia a potential partner. And they had hoped that shared fears of Tehran might help Israel forge ties with Riyadh.

Still, Israeli analysts of Iranian and Gulf affairs said that the deal was not entirely disastrous for Israeli interests. Although it undermines Israeli hopes of forming a regional alliance against Iran, it could, perhaps counterintuitively, still allow for greater cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Despite normalizing ties, Saudi Arabia may continue to view Iran as an adversary and could still consider a closer partnership with Israel, particularly on military and cybersecurity issues, as another way of blunting that threat.

Among some Israeli politicians, the announcement provoked introspection about their country’s internal divisions. Some said the re-establishment of Saudi-Iranian ties highlighted how domestic turmoil risked distracting the government from more urgent concerns, such as Iran.

What are the obstacles to a true thaw in relations?

Saudi Arabia and Iran are global leaders of the two largest sects of Islam, with Saudi Arabia considering itself the guardian of Sunnis and Iran assuming a similar role for Shiites.

Leaders in Tehran routinely criticize Saudi Arabia’s close ties with the United States, accusing the kingdom of doing the West’s bidding in the Middle East. And Iran, in an effort to enhance its own security and project influence, has heavily invested in building a network of armed militias across the region. Saudi Arabia considers that network a threat not only to its own security, but also to the broader regional order.

Other areas of stark disagreement include the role of Shiite militias in Iraq and Lebanon, which Iran supports to enhance its regional influence and Saudi Arabia says weakens those countries.

The future of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, whom the Saudis wanted to help topple and Iran has helped remain in power, is another dividing line.

How to resolve the war in Yemen is yet another major point of contention, with Iran backing the Houthi rebels, whose advances prompted Saudi Arabia to launch a broad military intervention into the conflict to try to push them back.

What could be behind the Saudi move?

For decades, Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy was relatively predictable. But Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman upended those expectations when he began rising to power in 2015, intervening in Yemen’s civil war, cutting ties with neighboring Qatar and in effect kidnapping Lebanon’s prime minister and pushing him to resign.

He has recently demonstrated a more pragmatic approach, mending the rift with Qatar, easing tensions with Turkey and pursuing peace talks in Yemen. The prince’s move toward regional reconciliation is partly driven by the challenges he faces at home as he tries to overhaul nearly every aspect of life in Saudi Arabia.

His “Vision 2030” plan calls for diversifying the oil-dependent economy by attracting tourism and foreign investment, drawing millions of expatriates to the kingdom and turning it into a global hub for business and culture. Calming regional tensions is central to that vision, but it is also driven by his desire to turn Saudi Arabia into a global power and make it less dependent on the United States.

That doesn’t mean replacing the United States, which still supplies the vast majority of Saudi Arabia’s weapons and defensive systems — at least not anytime soon. But the prince has been looking for ways to build deeper ties with other global powers, such as China, India and Russia.

Reporting was contributed by Vivian Nereim, David Pierson, Christopher Buckley, Michael Crowley, Patrick Kingsley and Zolan Kanno-Youngs.

Tinggalkan Balasan